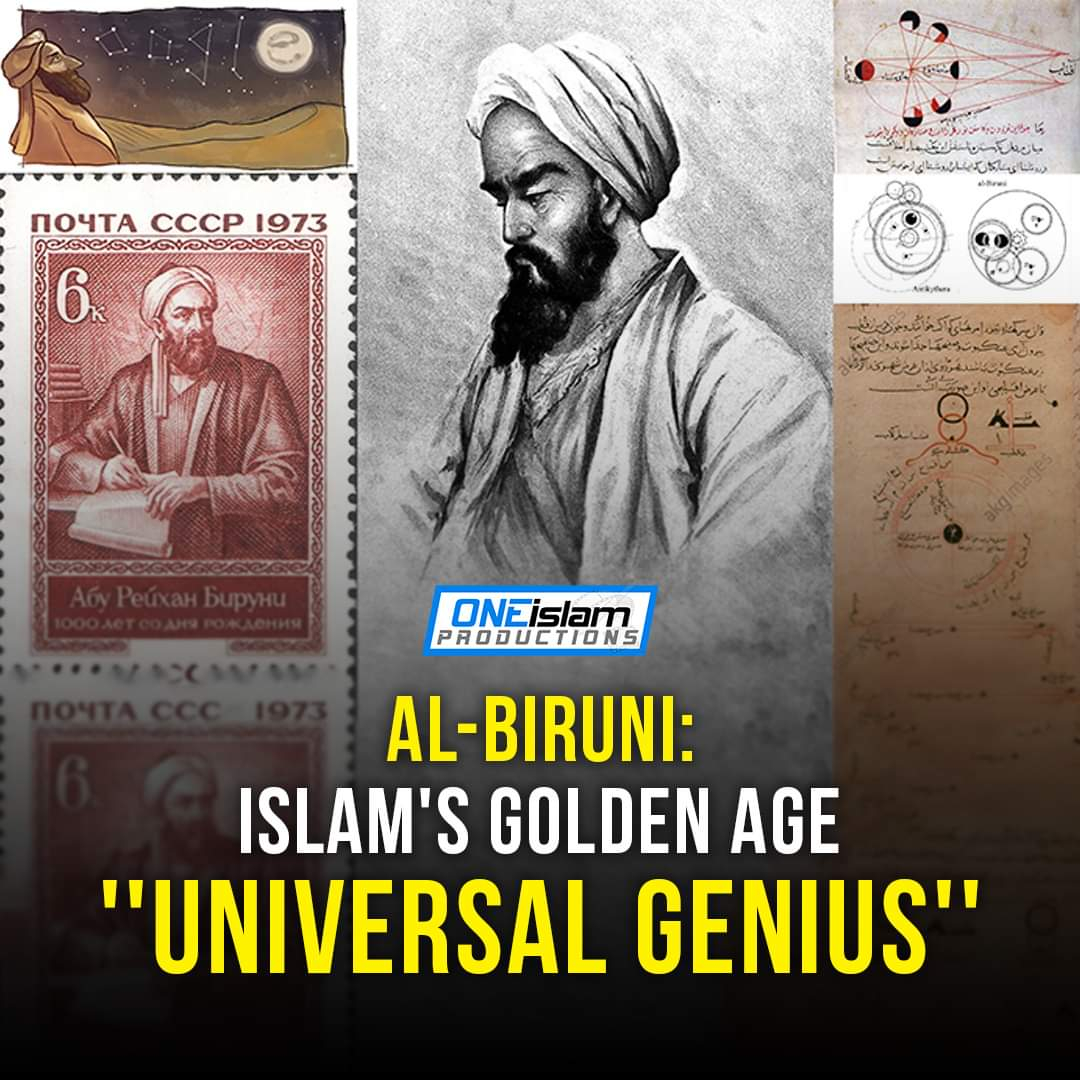

Calculating the radius of the earth over a thousand years ago required a lot of imagination. It was Abu Reyhan Al-Biruni, the 10th century Islamic mathematical genius, who combined trigonometry and algebra to achieve this very numerical feat.

Biruni’s scholarly legacy has inspired scientists and mathematicians for several centuries, and his name continues to command respect even today.

Scholars like Biruni were born at a time when much of the world’s scientific and mathematical knowledge was translated into Arabic. By the time he came of age, he was also introduced to concepts developed by scholars from different civilisations and centuries. From the scientific literature of the Babylonians to those of the Romans, to ancient Indian texts on astrology, Biruni learnt from it all. Like other Muslim scholars from the Golden Age of Islam, he was also hungry for knowledge.

According to the Turkish Professor, Fuat Sezgin, intellectually sound debates occurred between the 27-year-old Biruni and 18-year-old Ibn Sina. The two great minds are known to have discussed ‘The propagation of light and its measurement’ in a great depth. Sezgin, who died in 2018, concluded that the quality of those debates is rare and probably does not exist even today.

#oneislamproductions #oneislamreminders #islam #allah #islamicknowledge #subhanallah #islamicpost #muslim #beneficial #reminders #albiruni #goldenage #scientists #scholar #genius #universalgenius #explorepage

Biruni’s scholarly legacy has inspired scientists and mathematicians for several centuries, and his name continues to command respect even today.

Scholars like Biruni were born at a time when much of the world’s scientific and mathematical knowledge was translated into Arabic. By the time he came of age, he was also introduced to concepts developed by scholars from different civilisations and centuries. From the scientific literature of the Babylonians to those of the Romans, to ancient Indian texts on astrology, Biruni learnt from it all. Like other Muslim scholars from the Golden Age of Islam, he was also hungry for knowledge.

According to the Turkish Professor, Fuat Sezgin, intellectually sound debates occurred between the 27-year-old Biruni and 18-year-old Ibn Sina. The two great minds are known to have discussed ‘The propagation of light and its measurement’ in a great depth. Sezgin, who died in 2018, concluded that the quality of those debates is rare and probably does not exist even today.

#oneislamproductions #oneislamreminders #islam #allah #islamicknowledge #subhanallah #islamicpost #muslim #beneficial #reminders #albiruni #goldenage #scientists #scholar #genius #universalgenius #explorepage

Calculating the radius of the earth over a thousand years ago required a lot of imagination. It was Abu Reyhan Al-Biruni, the 10th century Islamic mathematical genius, who combined trigonometry and algebra to achieve this very numerical feat.

Biruni’s scholarly legacy has inspired scientists and mathematicians for several centuries, and his name continues to command respect even today.

Scholars like Biruni were born at a time when much of the world’s scientific and mathematical knowledge was translated into Arabic. By the time he came of age, he was also introduced to concepts developed by scholars from different civilisations and centuries. From the scientific literature of the Babylonians to those of the Romans, to ancient Indian texts on astrology, Biruni learnt from it all. Like other Muslim scholars from the Golden Age of Islam, he was also hungry for knowledge.

According to the Turkish Professor, Fuat Sezgin, intellectually sound debates occurred between the 27-year-old Biruni and 18-year-old Ibn Sina. The two great minds are known to have discussed ‘The propagation of light and its measurement’ in a great depth. Sezgin, who died in 2018, concluded that the quality of those debates is rare and probably does not exist even today.

#oneislamproductions #oneislamreminders #islam #allah #islamicknowledge #subhanallah #islamicpost #muslim #beneficial #reminders #albiruni #goldenage #scientists #scholar #genius #universalgenius #explorepage

0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos