Abbasi Halifeliği: Rönesans'ı Ateşleyen Bir Devrim

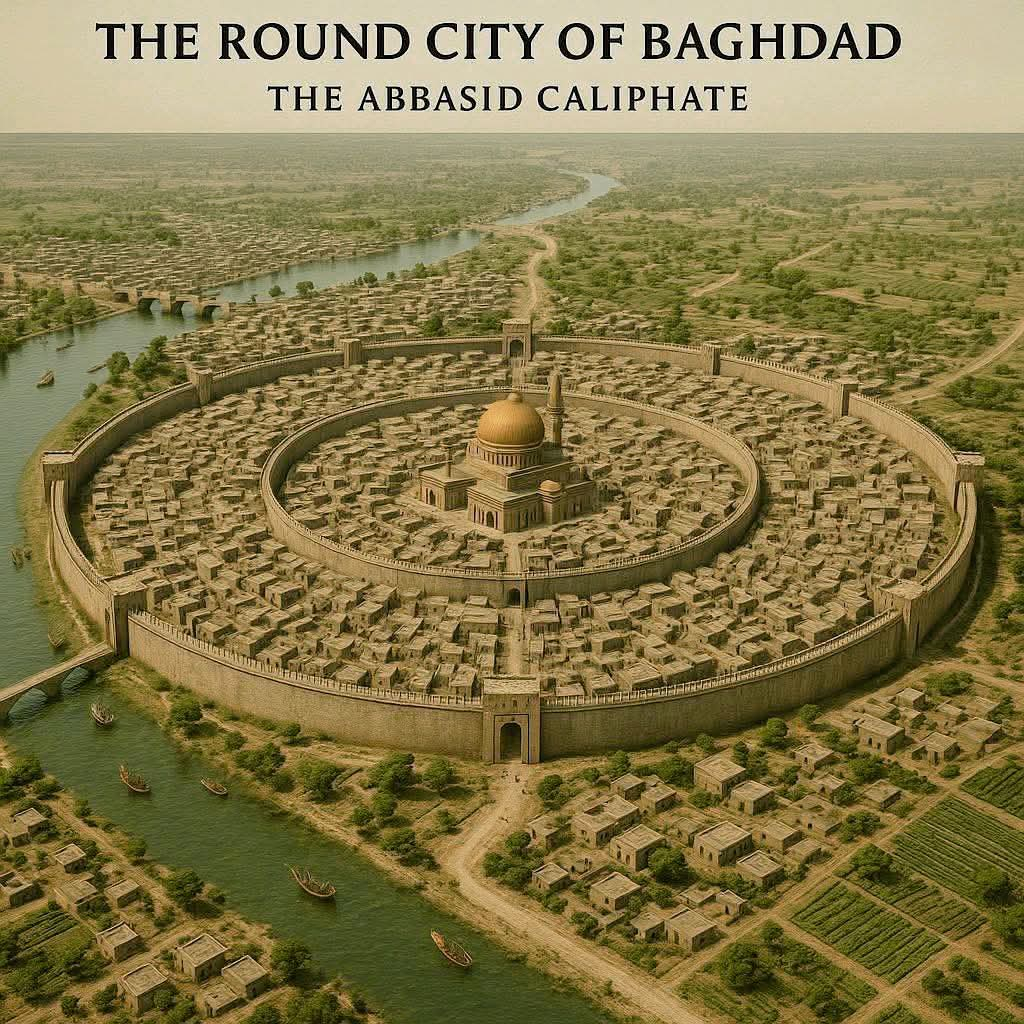

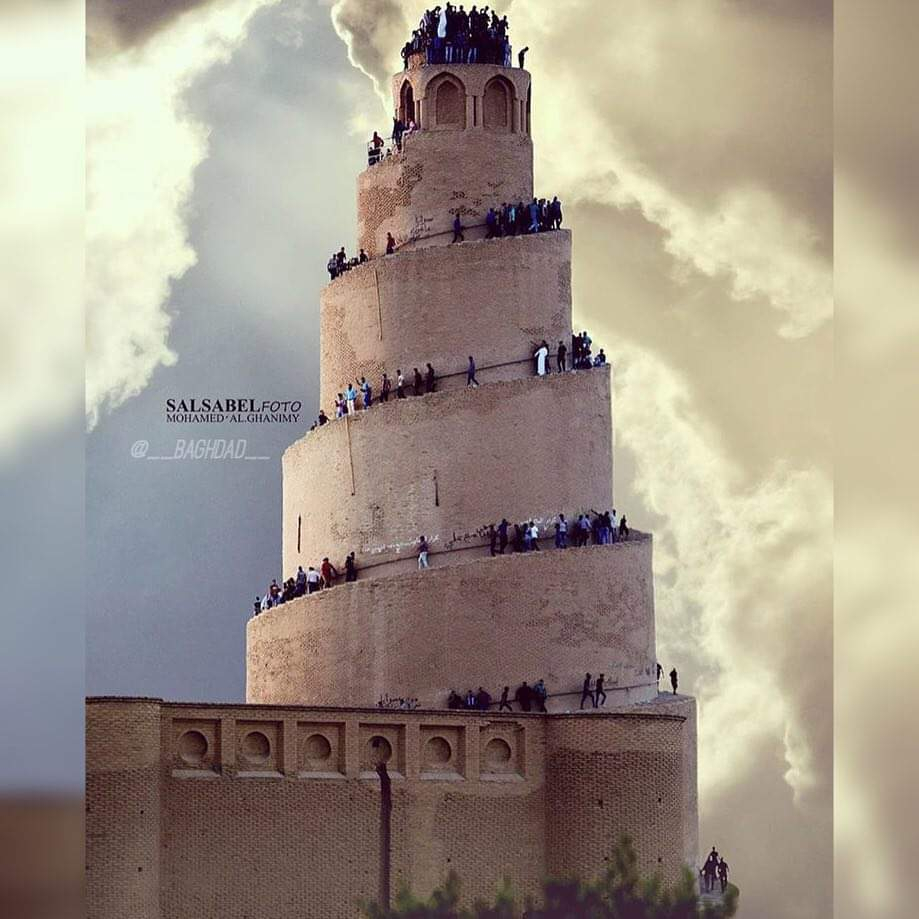

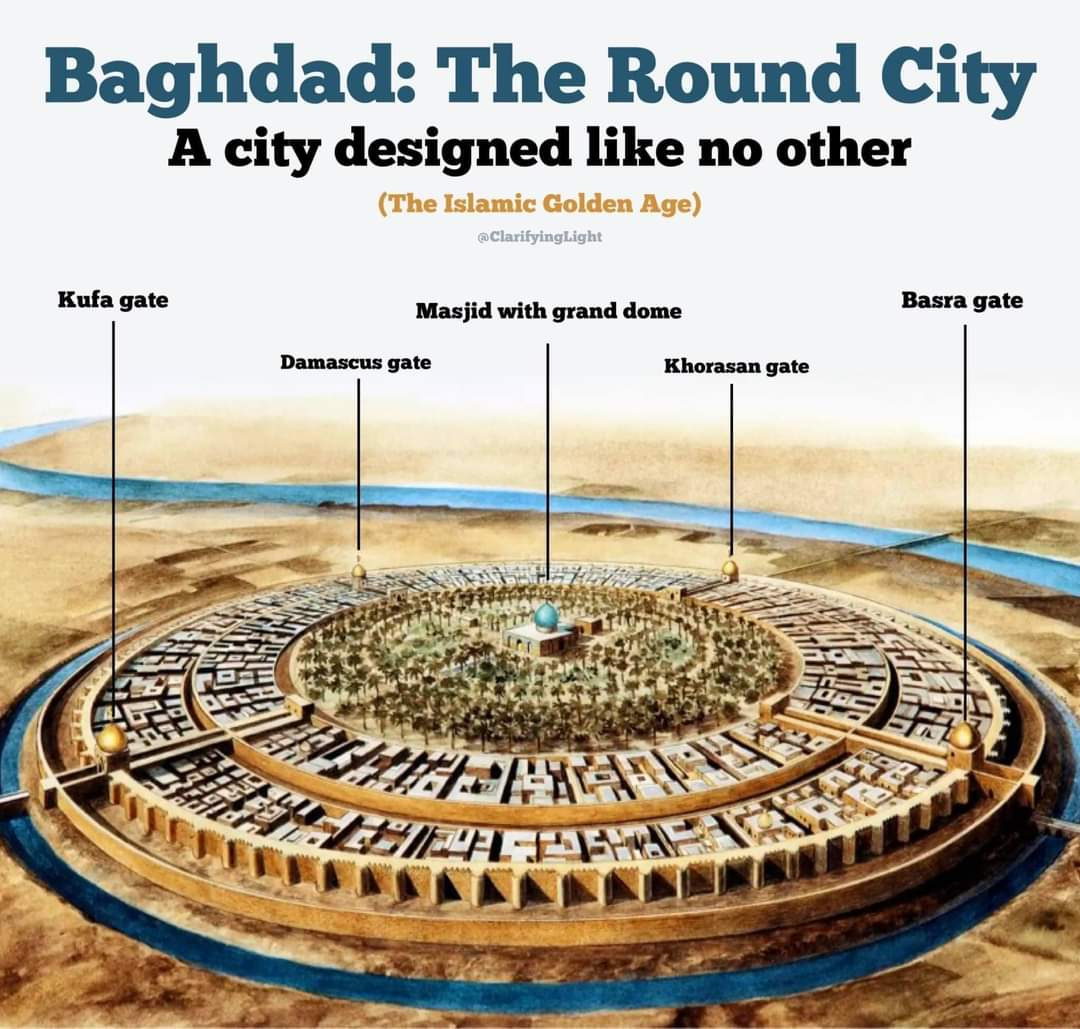

M.Ö. 750 yılında Abbasiler İslam'ın Altın Çağı'na öncülük ederek Umayadları devirdiler. İkonik Bağdat'taki "Yuvarlak Şehir"inden İslam dünyasını bilgi, kültür ve yenilikçi bir fenerine dönüştürdüler.

*Bağdat'ta Yeni Bir Çağ*

M.Ö. 762 yılında Halife Mansur tarafından kurulan Bağdat, Arapları, Farsları, Türkleri ve daha fazlasını canlı bir İslami kimlik altında birleştirerek küresel bir ticaret, diplomasi ve aklın merkezi haline geldi.

*Öğrenmenin Altın Çağı*

Harun el-Reşid ve el-Ma'mun gibi halifeler kültürel bir patlamayı körükledi:

*Bilgelik Evi* Yunanca, Farsça ve Hint metinlerini tercüme etti.

Harezmi cebiri icat etti, El-Razi tıbbı devrim yaptı ve İbn Sina'nın *Tıp Kanonu* küresel sağlık hizmetini şekillendirdi.

El-Hasan ibn el-Heysem optiğe öncülük etti, bilimsel yöntemin temelini attı.

*Sanat ve Felsefe gelişti*

El-Mutanabbi gibi şairler, Sufi mistikleri ve El-Farabi gibi filozoflar Yunan rasyonalizmini İslam düşüncesiyle harmanlamışlardır. Abbasi mahkemesi ipek, müzik ve kütüphanelerle göz kamaştırdı.

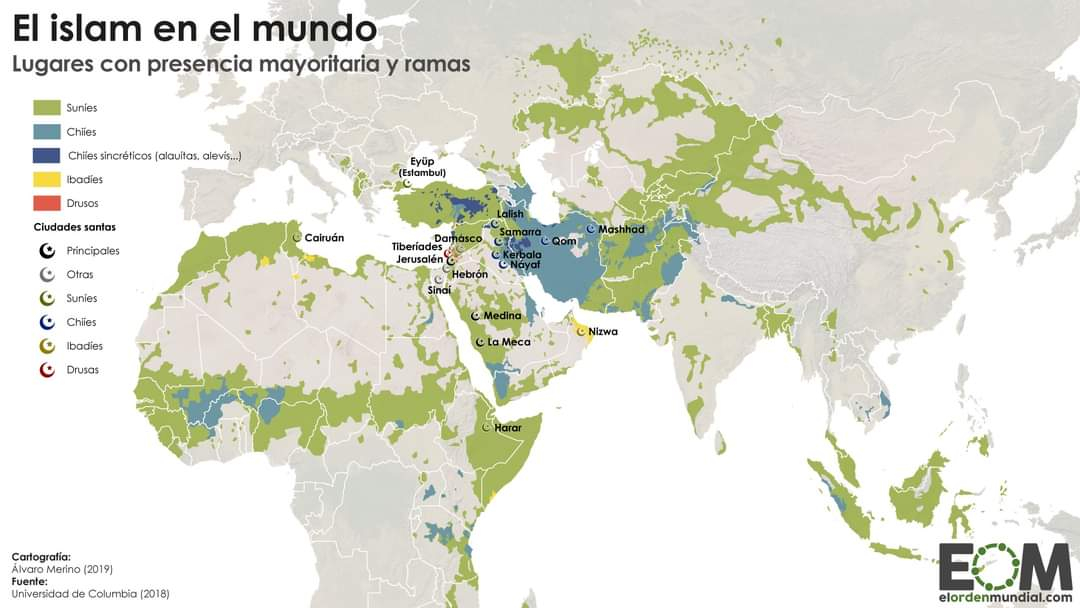

*Dini Çeşitlilik*

Abbasiler Sünni İslam'ı teşvik ederken Şii, Haricit ve İsmail düşüncelerinin yükselişini gördüler ve ilahiyat okullarının zengin bir duvar halısını beslediler.

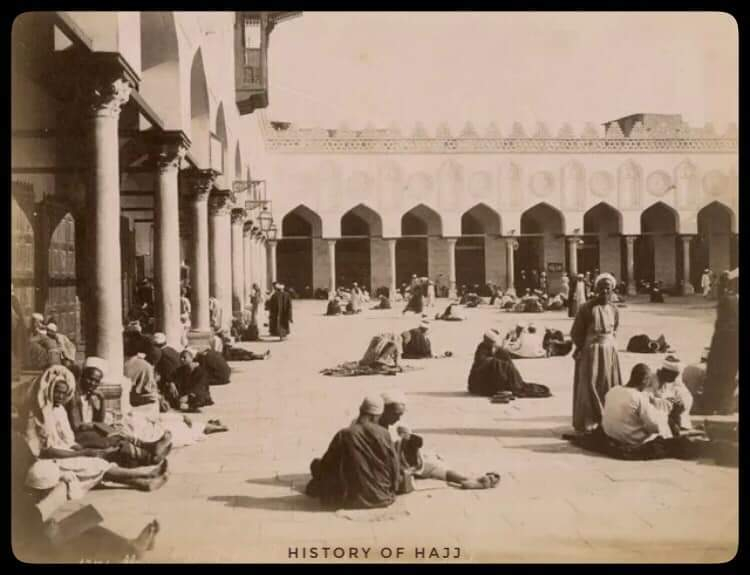

*Reddet ve Miras*

10. yüzyıla kadar, parçalanma başladı. 1258 yılında Bağdat'ın Moğol çuvallaması ve vilayet hanedanları Altın Çağ'ı sonlandırdı. Ancak Abbasilerin mirası 1517 yılına kadar Kahire'nin sembolik halifeliğinde yaşadı.

*Bir Medeni Güç*

Abbasiler antik bilgeliği, kaynaşmış kültürleri ve Avrupa Rönesansına ilham vermişlerdir. Hikayeleri kalemin kılıçtan daha güçlü olduğunu kanıtlıyor.

#AbbasidCaliphate #IslamicGoldenAge #HouseOfWisdom #Baghdad #IslamicHistory #HistoryMatters #ScienceAndCulture #MedievalHistory #ZaneHistoryBuff #theinsidehistory

M.Ö. 750 yılında Abbasiler İslam'ın Altın Çağı'na öncülük ederek Umayadları devirdiler. İkonik Bağdat'taki "Yuvarlak Şehir"inden İslam dünyasını bilgi, kültür ve yenilikçi bir fenerine dönüştürdüler.

*Bağdat'ta Yeni Bir Çağ*

M.Ö. 762 yılında Halife Mansur tarafından kurulan Bağdat, Arapları, Farsları, Türkleri ve daha fazlasını canlı bir İslami kimlik altında birleştirerek küresel bir ticaret, diplomasi ve aklın merkezi haline geldi.

*Öğrenmenin Altın Çağı*

Harun el-Reşid ve el-Ma'mun gibi halifeler kültürel bir patlamayı körükledi:

*Bilgelik Evi* Yunanca, Farsça ve Hint metinlerini tercüme etti.

Harezmi cebiri icat etti, El-Razi tıbbı devrim yaptı ve İbn Sina'nın *Tıp Kanonu* küresel sağlık hizmetini şekillendirdi.

El-Hasan ibn el-Heysem optiğe öncülük etti, bilimsel yöntemin temelini attı.

*Sanat ve Felsefe gelişti*

El-Mutanabbi gibi şairler, Sufi mistikleri ve El-Farabi gibi filozoflar Yunan rasyonalizmini İslam düşüncesiyle harmanlamışlardır. Abbasi mahkemesi ipek, müzik ve kütüphanelerle göz kamaştırdı.

*Dini Çeşitlilik*

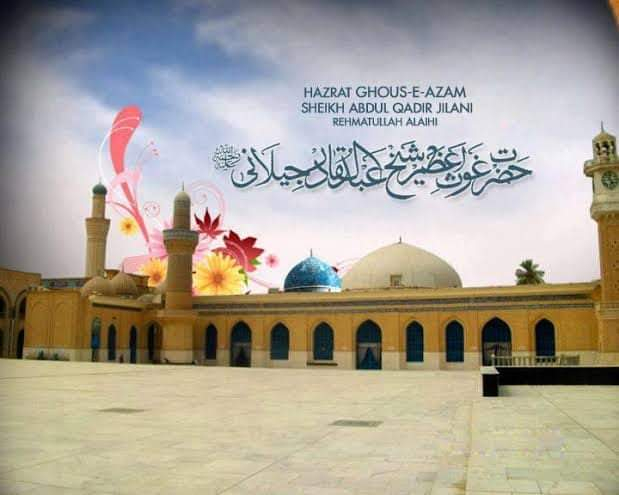

Abbasiler Sünni İslam'ı teşvik ederken Şii, Haricit ve İsmail düşüncelerinin yükselişini gördüler ve ilahiyat okullarının zengin bir duvar halısını beslediler.

*Reddet ve Miras*

10. yüzyıla kadar, parçalanma başladı. 1258 yılında Bağdat'ın Moğol çuvallaması ve vilayet hanedanları Altın Çağ'ı sonlandırdı. Ancak Abbasilerin mirası 1517 yılına kadar Kahire'nin sembolik halifeliğinde yaşadı.

*Bir Medeni Güç*

Abbasiler antik bilgeliği, kaynaşmış kültürleri ve Avrupa Rönesansına ilham vermişlerdir. Hikayeleri kalemin kılıçtan daha güçlü olduğunu kanıtlıyor.

#AbbasidCaliphate #IslamicGoldenAge #HouseOfWisdom #Baghdad #IslamicHistory #HistoryMatters #ScienceAndCulture #MedievalHistory #ZaneHistoryBuff #theinsidehistory

🏛️ Abbasi Halifeliği: Rönesans'ı Ateşleyen Bir Devrim 🌟

M.Ö. 750 yılında Abbasiler İslam'ın Altın Çağı'na öncülük ederek Umayadları devirdiler. İkonik Bağdat'taki "Yuvarlak Şehir"inden İslam dünyasını bilgi, kültür ve yenilikçi bir fenerine dönüştürdüler. 🕌✨

🌍 *Bağdat'ta Yeni Bir Çağ*

M.Ö. 762 yılında Halife Mansur tarafından kurulan Bağdat, Arapları, Farsları, Türkleri ve daha fazlasını canlı bir İslami kimlik altında birleştirerek küresel bir ticaret, diplomasi ve aklın merkezi haline geldi.

💡 *Öğrenmenin Altın Çağı*

Harun el-Reşid ve el-Ma'mun gibi halifeler kültürel bir patlamayı körükledi:

🧠 *Bilgelik Evi* Yunanca, Farsça ve Hint metinlerini tercüme etti.

📚 Harezmi cebiri icat etti, El-Razi tıbbı devrim yaptı ve İbn Sina'nın *Tıp Kanonu* küresel sağlık hizmetini şekillendirdi.

🔬 El-Hasan ibn el-Heysem optiğe öncülük etti, bilimsel yöntemin temelini attı.

🎭 *Sanat ve Felsefe gelişti*

El-Mutanabbi gibi şairler, Sufi mistikleri ve El-Farabi gibi filozoflar Yunan rasyonalizmini İslam düşüncesiyle harmanlamışlardır. Abbasi mahkemesi ipek, müzik ve kütüphanelerle göz kamaştırdı. 🎵🎶

🕌 *Dini Çeşitlilik*

Abbasiler Sünni İslam'ı teşvik ederken Şii, Haricit ve İsmail düşüncelerinin yükselişini gördüler ve ilahiyat okullarının zengin bir duvar halısını beslediler.

🗣️ *Reddet ve Miras*

10. yüzyıla kadar, parçalanma başladı. 1258 yılında Bağdat'ın Moğol çuvallaması ve vilayet hanedanları Altın Çağ'ı sonlandırdı. Ancak Abbasilerin mirası 1517 yılına kadar Kahire'nin sembolik halifeliğinde yaşadı.

🌙 *Bir Medeni Güç*

Abbasiler antik bilgeliği, kaynaşmış kültürleri ve Avrupa Rönesansına ilham vermişlerdir. Hikayeleri kalemin kılıçtan daha güçlü olduğunu kanıtlıyor. ✍️ 💡

#AbbasidCaliphate #IslamicGoldenAge #HouseOfWisdom #Baghdad #IslamicHistory #HistoryMatters #ScienceAndCulture #MedievalHistory #ZaneHistoryBuff #theinsidehistory

0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos